Reddit mentions: The best astrophysics & space science books

We found 643 Reddit comments discussing the best astrophysics & space science books. We ran sentiment analysis on each of these comments to determine how redditors feel about different products. We found 119 products and ranked them based on the amount of positive reactions they received. Here are the top 20.

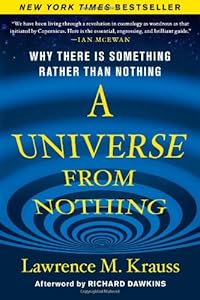

1. A Universe from Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather than Nothing

- Atria Books

Features:

Specs:

| Height | 8.375 Inches |

| Length | 5.5 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | January 2013 |

| Weight | 0.45 Pounds |

| Width | 0.7 Inches |

2. A Universe from Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather than Nothing

an engrossing tour of current cosmology

Specs:

| Height | 8.999982 Inches |

| Length | 5.999988 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | January 2012 |

| Weight | 0.86 pounds |

| Width | 0.8999982 Inches |

3. The Grand Design

- grand

- Stephen Hawking

- design

- stephen

- non fiction

Features:

Specs:

| Color | Black |

| Height | 9.29 Inches |

| Length | 6.27 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | September 2010 |

| Weight | 1.3 Pounds |

| Width | 0.81 Inches |

4. The Grand Design

- Bantam

Features:

Specs:

| Color | Black |

| Height | 9.02 Inches |

| Length | 6.03 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | February 2012 |

| Weight | 0.97 Pounds |

| Width | 0.54 Inches |

5. Black Holes and Time Warps: Einstein's Outrageous Legacy (Commonwealth Fund Book Program)

W W Norton Company

Specs:

| Color | White |

| Height | 9.3 Inches |

| Length | 6.1 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | January 1995 |

| Weight | 1.26324876126 Pounds |

| Width | 1.1 Inches |

6. A First Course in General Relativity

Cambridge University Press

Specs:

| Height | 10 Inches |

| Length | 8 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Weight | 2.2266688462 Pounds |

| Width | 0.94 Inches |

7. Quantum Mechanics: The Theoretical Minimum

- Basic Books AZ

Features:

Specs:

| Height | 8.25 Inches |

| Length | 5.5 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | May 2015 |

| Weight | 0.88625829324 pounds |

| Width | 0.96 Inches |

8. The Fabric of Reality: The Science of Parallel Universes--and Its Implications

- Cold-weather boot with waterproof upper featuring removable 8mm thermal-guard liner and hook-and-loop strap

- Drawstring at top line

- Height: 14.25 inches

- Weight: 4.1 lbs per pair

- Flexible in all temperatures for a better grip in snow

Features:

Specs:

| Color | Black |

| Height | 7.9 Inches |

| Length | 5.3 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | August 1998 |

| Weight | 0.72 Pounds |

| Width | 0.88 Inches |

9. Foundations of Astrophysics

- ELAND

Features:

Specs:

| Height | 9.5 Inches |

| Length | 7.7 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Weight | 2.425084882 Pounds |

| Width | 1.2 Inches |

10. The Hidden Reality: Parallel Universes and the Deep Laws of the Cosmos

- Vintage Books

Features:

Specs:

| Color | Black |

| Height | 0.93 Inches |

| Length | 8.04 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | November 2011 |

| Weight | 0.95 Pounds |

| Width | 5.29 Inches |

11. The Road to Reality : A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe

Used Book in Good Condition

Specs:

| Height | 9.44 Inches |

| Length | 6.63 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | February 2005 |

| Weight | 3.305 Pounds |

| Width | 2.23 Inches |

12. A Universe from Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather than Nothing

- SHAVING ESSENTIAL - This set includes everything you need to get started.

- BOAR BRUSH - The set comes with a 10065 pure bristle brush from Omega.

- SHAVING SOAP - The set also includes a 150 ml classic shaving soap with eucalyptus oil for a refreshing shave.

- MAKES A GREAT PRESENT - This boxed set makes an excellent present for men.

Features:

Specs:

| Release date | January 2012 |

13. Parallel Worlds: A Journey Through Creation, Higher Dimensions, and the Future of the Cosmos

- Anchor

Features:

Specs:

| Color | Multicolor |

| Height | 7.82 Inches |

| Length | 5.86 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | February 2006 |

| Weight | 0.89 Pounds |

| Width | 0.91 Inches |

14. DIV, Grad, Curl, and All That: An Informal Text on Vector Calculus

Specs:

| Height | 9.5 Inches |

| Length | 6.25 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Weight | 0.6172943336 Pounds |

| Width | 0.5 Inches |

15. Gravitation

Specs:

| Height | 9.9 Inches |

| Length | 7.9 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | October 2017 |

| Weight | 6.00098277164 Pounds |

| Width | 2.2 Inches |

16. The Hidden Reality: Parallel Universes and the Deep Laws of the Cosmos

170 pages

Specs:

| Height | 9.64 Inches |

| Length | 6.56 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | January 2011 |

| Weight | 1.65 Pounds |

| Width | 1.36 Inches |

17. Relativity: The Special and the General Theory

Three Rivers Press CA

Specs:

| Color | White |

| Height | 7.97 Inches |

| Length | 5.16 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | June 1995 |

| Weight | 0.34 Pounds |

| Width | 0.46 Inches |

18. Relativity: The Special And The General Theory

Used Book in Good Condition

Specs:

| Height | 8.98 Inches |

| Length | 5.91 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Release date | December 2010 |

| Weight | 0.5291094288 Pounds |

| Width | 0.39 Inches |

19. General Relativity: An Introduction for Physicists

Specs:

| Height | 9.61 Inches |

| Length | 6.69 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Weight | 2.91230648102 Pounds |

| Width | 1.25 Inches |

20. The Illustrated A Brief History of Time / The Universe in a Nutshell - Two Books in One

(shelf 16.1.3)

Specs:

| Height | 1 Inches |

| Length | 7 Inches |

| Number of items | 1 |

| Weight | 3.52 Pounds |

| Width | 5 Inches |

🎓 Reddit experts on astrophysics & space science books

The comments and opinions expressed on this page are written exclusively by redditors. To provide you with the most relevant data, we sourced opinions from the most knowledgeable Reddit users based the total number of upvotes and downvotes received across comments on subreddits where astrophysics & space science books are discussed. For your reference and for the sake of transparency, here are the specialists whose opinions mattered the most in our ranking.

Friend asked for a similar list a while ago and I put this together. Would love to see people thoughts/feedback.

Very High Level Introductions:

Deeper Pop-sci Dives (probably in this order):

Blending the line between pop-sci and mathematical (these books are not meant to be read and put away but instead read, re-read and pondered):

I'd like to give you my two cents as well on how to proceed here. If nothing else, this will be a second opinion. If I could redo my physics education, this is how I'd want it done.

If you are truly wanting to learn these fields in depth I cannot stress how important it is to actually work problems out of these books, not just read them. There is a certain understanding that comes from struggling with problems that you just can't get by reading the material. On that note, I would recommend getting the Schaum's outline to whatever subject you are studying if you can find one. They are great books with hundreds of solved problems and sample problems for you to try with the answers in the back. When you get to the point you can't find Schaums anymore, I would recommend getting as many solutions manuals as possible. The problems will get very tough, and it's nice to verify that you did the problem correctly or are on the right track, or even just look over solutions to problems you decide not to try.

Basics

I second Stewart's Calculus cover to cover (except the final chapter on differential equations) and Halliday, Resnick and Walker's Fundamentals of Physics. Not all sections from HRW are necessary, but be sure you have the fundamentals of mechanics, electromagnetism, optics, and thermal physics down at the level of HRW.

Once you're done with this move on to studying differential equations. Many physics theorems are stated in terms of differential equations so really getting the hang of these is key to moving on. Differential equations are often taught as two separate classes, one covering ordinary differential equations and one covering partial differential equations. In my opinion, a good introductory textbook to ODEs is one by Morris Tenenbaum and Harry Pollard. That said, there is another book by V. I. Arnold that I would recommend you get as well. The Arnold book may be a bit more mathematical than you are looking for, but it was written as an introductory text to ODEs and you will have a deeper understanding of ODEs after reading it than your typical introductory textbook. This deeper understanding will be useful if you delve into the nitty-gritty parts of classical mechanics. For partial differential equations I recommend the book by Haberman. It will give you a good understanding of different methods you can use to solve PDEs, and is very much geared towards problem-solving.

From there, I would get a decent book on Linear Algebra. I used the one by Leon. I can't guarantee that it's the best book out there, but I think it will get the job done.

This should cover most of the mathematical training you need to move onto the intermediate level physics textbooks. There will be some things that are missing, but those are usually covered explicitly in the intermediate texts that use them (i.e. the Delta function). Still, if you're looking for a good mathematical reference, my recommendation is Lua. It may be a good idea to go over some basic complex analysis from this book, though it is not necessary to move on.

Intermediate

At this stage you need to do intermediate level classical mechanics, electromagnetism, quantum mechanics, and thermal physics at the very least. For electromagnetism, Griffiths hands down. In my opinion, the best pedagogical book for intermediate classical mechanics is Fowles and Cassidy. Once you've read these two books you will have a much deeper understanding of the stuff you learned in HRW. When you're going through the mechanics book pay particular attention to generalized coordinates and Lagrangians. Those become pretty central later on. There is also a very old book by Robert Becker that I think is great. It's problems are tough, and it goes into concepts that aren't typically covered much in depth in other intermediate mechanics books such as statics. I don't think you'll find a torrent for this, but it is 5 bucks on Amazon. That said, I don't think Becker is necessary. For quantum, I cannot recommend Zettili highly enough. Get this book. Tons of worked out examples. In my opinion, Zettili is the best quantum book out there at this level. Finally for thermal physics I would use Mandl. This book is merely sufficient, but I don't know of a book that I liked better.

This is the bare minimum. However, if you find a particular subject interesting, delve into it at this point. If you want to learn Solid State physics there's Kittel. Want to do more Optics? How about Hecht. General relativity? Even that should be accessible with Schutz. Play around here before moving on. A lot of very fascinating things should be accessible to you, at least to a degree, at this point.

Advanced

Before moving on to physics, it is once again time to take up the mathematics. Pick up Arfken and Weber. It covers a great many topics. However, at times it is not the best pedagogical book so you may need some supplemental material on whatever it is you are studying. I would at least read the sections on coordinate transformations, vector analysis, tensors, complex analysis, Green's functions, and the various special functions. Some of this may be a bit of a review, but there are some things Arfken and Weber go into that I didn't see during my undergraduate education even with the topics that I was reviewing. Hell, it may be a good idea to go through the differential equations material in there as well. Again, you may need some supplemental material while doing this. For special functions, a great little book to go along with this is Lebedev.

Beyond this, I think every physicist at the bare minimum needs to take graduate level quantum mechanics, classical mechanics, electromagnetism, and statistical mechanics. For quantum, I recommend Cohen-Tannoudji. This is a great book. It's easy to understand, has many supplemental sections to help further your understanding, is pretty comprehensive, and has more worked examples than a vast majority of graduate text-books. That said, the problems in this book are LONG. Not horrendously hard, mind you, but they do take a long time.

Unfortunately, Cohen-Tannoudji is the only great graduate-level text I can think of. The textbooks in other subjects just don't measure up in my opinion. When you take Classical mechanics I would get Goldstein as a reference but a better book in my opinion is Jose/Saletan as it takes a geometrical approach to the subject from the very beginning. At some point I also think it's worth going through Arnold's treatise on Classical. It's very mathematical and very difficult, but I think once you make it through you will have as deep an understanding as you could hope for in the subject.

Thank you for the effort! I'll try to do you justice with a thorough response.

----

> 1. God says what he needs to say to us through the Bible.

Sure it's the Bible and not Harry Potter? To anyone without your obvious bias, the Bible looks like a collection of fanciful but poorly edited fiction. God's message hasn't reached me and it hasn't reached 5 billion other humans alone among the living. In other words, if this is an omnipotent's idea of effective communication, God sucks as a communicator.

> 2. God is not inert, he sometimes does miracles

Prove this and I'll leave you alone. Has God ever healed an amputee? Has God ever accomplished a miracle that has no natural explanation?

No wait, references to the work of fiction mentioned in #1 don't count. There is not the slightest bit of evidence that your precious Bible is anything more than a stack of useful rolling papers. I've addressed this before. J.K. Rowling has Harry Potter performing scores of miracles in her books, it's really easy to create a miracle with pen and paper.

> 3. The evidence is not inadequate. If you want evidence of his existence, there is evidence everywhere, and in sheer necessity, it is pointed out that God must exist.

So you say. Your following arguments are... sorely lacking. Here we go:

> 3.1 The need of a creator

If you saw a car in the forest, you wouldn't say it randomly came into existence and over time came together by itself, because it is too complex for that to have happened.

Correct. That's easy for me to say because I know exactly what a car is and how it's made.

> In the same way, this universe and everything in it is far too complex to randomly explode into existence and come together by itself, a creator is needed and that creator is God.

Your analogy doesn't hold. The universe is not very complex conceptually, it's been satisfactorily explained how all heavenly bodies resulted from the expansion of space followed by the clumping of clouds of primeval hydrogen. Suns and the nuclear process in them? A natural consequence of packing a lot of hydrogen with gravity. Heavy elements? The ashes of nuclear fusion. Planets circling around suns? That's what happens when heavenly bodies nearly collide in a vacuum, influenced only by each other's gravity. Finally, the complexity of life on earth is neatly explained by evolution from very primitive beginnings from substances that occur -naturally- in the void of lifeless space. No magic is required to explain any of this. But I see we get to talk about this in greater depth in #4.

Still, for your interest, this video refutes Craig's Kalam Cosmological argument and is thoroughly captivating while presenting modern cosmology. Highly recommended!

> 3.2 The need for an original mover/causer

You know nothing moves by itself correct?

No, I don't know this, because I have a solid education in physics. Atomic nuclei spontaneously explode and particles fly from them - movement without a mover. Plato's Prime Mover argument dates back to a time when people didn't know anything about physics and science was done by sitting on your butt, guessing and thinking.

> 3.3 The need of a standard

When you call something, for instance let's say "good", there has to be a standard upon which good is based.

This response of yours -so far- is sounding suspiciously like a copy of a William Lane Craig debate argument. Please note that all of his arguments have been successfully refuted - though not necessarily within one debate or only within debates. But regardless, I can easily address your arguments on my own.

Now then. Basic moral behavior has been shown to emerge naturally as a result of evolution. Yes, this is why theists hate evolution so much. It explains a lot of stuff that used to be attributed to God. Animals in the wild show moral behavior such as altruism, fairness, love, cooperation, justice and so forth. Even robot simulations, given only the most minimal initial instructions, develop "moral" behavior because that turns out to be a successful selection criteria for survival.

If you try to point out that humans display and think about much more complex moral situations than animals, I'll agree. But you know who invented those extensions of purely survival-oriented moral behavior? Humans did, not God. Humans look at the behaviors that promote survival and well-being in animals and humans and call it "good." They see behavior that hurts and kills animals and people and makes them suffer, and they call it "bad." Your five year old kid can grasp this concept - you insult your god when you claim this is so difficult it necessarily requires divine intervention. I recommend Peter Singer's book Practical Ethics, a thoughtful and thorough discussion of morals far more nuanced and acceptable to a modern society than the barbaric postulates of scripture. Rape a virgin, buy her as a wife for 50 shekels, indeed!

> 4.1 About the Origin of Life/Finely tuning a killer cosmos

> Anyway, for life to come together even by accident, you would need matter

Correct.

> now the universe is not infinite and even scientists know that.

I'm not sure that's certain, but it's probably irrelevant. Let's move on.

> that scientists say made the universe would need matter present.

Correct. We certainly observe a helluva lot of matter in the present-day universe (to the extent we can observe it).

> Where do you expect that matter to have come from?

An empty geometry and some very basic laws of physics (including quantum physics). This is very un-intuitive, which is why people restricted to Platonic thinking have trouble with it. But you know that matter and energy are equivalent, via E=mc^2 , right? Given the raw physics of the very early universe, matter could be created from energy and vice versa. OK, that still doesn't explain where the (matter+energy) came from. Here's the fun part: it turns out that the universe contains not just the conventional "positive" energy we're familiar with, but also negative energy. And it turns out that the sum of (matter + positive energy) on one hand and (negative energy) on the other are exactly equal and cancel out. In other words, and this is important, the creation of the universe incurred no net "cost" in matter or energy. This being the case, it becomes similarly plausible for for the entire universe to have spontaneously popped into existence just like those sub-atomic particles that cause the Casimir Effect. Stephen Hawking has explained this eloquently in his book The Grand Design but you may prefer Lawrence Krauss' engaging lecture A Universe From Nothing.

> I know for a fact that people are smarter than an explosion and even they have been unsuccessful in making organic life forms from scratch

Wrong again. It took them 15 years, but Craig Venter and his project recently succeeded in constructing the first self-replicating synthetic bacterial cell.

By way of interest, people making the kind of claims you do were similarly amazed when Friedrich Wöhler, in 1828, synthesized the first chemical compound, urea, that is otherwise only created by living beings. This achievement torpedoed the Vital Force theory dating back to Galen. Yet another job taken off God's hands.

> let alone have them survive the forming of a planet.

Now this is just dumb. First the planet formed, then it cooled down a bit, then life developed.

> Because of that, I doubt an explosion could do it either.

So you're right there: The explosion just created the planet and the raw materials. Life later arose on the planet.

> Chance doesn't make matter pop into existence.

Yes it does. The effect I was mentioning earlier is called quantum fluctuation.

> 4.2 The human brain

(skipping the comparison of man with god. I don't see it contributing anything. All of this postulating doesn't make God plausible in any way)

> 4.3 The Original Christian Cosmos

> 4.3.1. Maybe because we are after the fall, we have already lost that perfect original cosmos Paul imagined.

Wait, this contradicts your next point.

> 4.3.2 You have to give Paul some credit for trying. He didn't have any the information or technology we have today.

Thank you, this confirms my assertion that the Bible and its authors contain no divinely inspired knowledge. The Bible is a collection of writings by people who thought you could cleanse leprosy by killing a couple of pigeons.

Now, about that original cosmos: either Paul was too uneducated to conceive the cosmos as it really exists, or what he imagined is irrelevant. In any case, what you consider the "after loss" cosmos is trillions of times larger than Paul imagined; it would be silly to call this a loss.

The fact remains that the world as described in the Bible is a pitiful caricature of the world as it is known today. And Carrier's main point remains that our cosmos is incredibly hostile to life; and if man were indeed God's favorite creation, the immensity of the cosmos would be a complete waste if it only served as a backdrop for our tiny little planet.

On science and evolution:

Genetics is where it's at. There is a ton of good fossil evidence, but genetics actually proves it on paper. Most books you can get through your local library (even by interlibrary loan) so you don't have to shell out for them just to read them.

Books:

The Making of the Fittest outlines many new forensic proofs of evolution. Fossil genes are an important aspect... they prove common ancestry. Did you know that humans have the gene for Vitamin C synthesis? (which would allow us to synthesize Vitamin C from our food instead of having to ingest it directly from fruit?) Many mammals have the same gene, but through a mutation, we lost the functionality, but it still hangs around.

Deep Ancestry proves the "out of Africa" hypothesis of human origins. It's no longer even a debate. MtDNA and Y-Chromosome DNA can be traced back directly to where our species began.

To give more rounded arguments, Hitchens can't be beat: God Is Not Great and The Portable Atheist (which is an overview of the best atheist writings in history, and one which I cannot recommend highly enough). Also, Dawkin's book The Greatest Show on Earth is a good overview of evolution.

General science: Stephen Hawking's books The Grand Design and A Briefer History of Time are excellent for laying the groundwork from Newtonian physics to Einstein's relativity through to the modern discovery of Quantum Mechanics.

Bertrand Russell and Thomas Paine are also excellent sources for philosophical, humanist, atheist thought; but they are included in the aforementioned Portable Atheist... but I have read much of their writings otherwise, and they are very good.

Also a subscription to a good peer-reviewed journal such as Nature is awesome, but can be expensive and very in depth.

Steven Pinker's The Blank Slate is also an excellent look at the human mind and genetics. To understand how the mind works, is almost your most important tool. If you know why people say the horrible things they do, you can see their words for what they are... you can see past what they say and see the mechanisms behind the words.

I've also been studying Zen for about a year. It's non-theistic and classed as "eastern philosophy". The Way of Zen kept me from losing my mind after deconverting and then struggling with the thought of a purposeless life and no future. I found it absolutely necessary to root out the remainder of the harmful indoctrination that still existed in my mind; and finally allowed me to see reality as it is instead of overlaying an ideology or worldview on everything.

Also, learn about the universe. Astronomy has been a useful tool for me. I can point my telescope at a galaxy that is more than 20 million light years away and say to someone, "See that galaxy? It took over 20 million years for the light from that galaxy to reach your eye." Creationists scoff at millions of years and say that it's a fantasy; but the universe provides real proof of "deep time" you can see with your own eyes.

Videos:

I recommend books first, because they are the best way to learn, but there are also very good video series out there.

BestofScience has an amazing series on evolution.

AronRa's Foundational Falsehoods of Creationism is awesome.

Thunderfoot's Why do people laugh at creationists is good.

Atheistcoffee's Why I am no longer a creationist is also good.

Also check out TheraminTrees for more on the psychology of religion; Potholer54 on The Big Bang to Us Made Easy; and Evid3nc3's series on deconversion.

Also check out the Evolution Documentary Youtube Channel for some of the world's best documentary series on evolution and science.

I'm sure I've overlooked something here... but that's some stuff off the top of my head. If you have any questions about anything, or just need to talk, send me a message!

Yes, I do believe it is by chance and I don't believe one needs to posit a god as the creator of the universe to explain its existence. And if one does, then where did that god come from?

E.g., one could explain the existence of the universe as the eminent theoretical physicist and cosmologist Steven Hawking did in The Grand Design.

>In his latest book, The Grand Design, an extract of which is published in Eureka magazine in The Times, Hawking said: “Because there is a law such as gravity, the Universe can and will create itself from nothing. Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing, why the Universe exists, why we exist.”

>

>He added: “It is not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touch paper and set the Universe going.”

Source: Stephen Hawking: God was not needed to create the Universe

I know it is hard for many people to accept that chance is involved in our existence. The theoretical physicist Albert Einstein is reputed to have remarked about God in relation to quantum mechanics that "I, at any rate, am convinced that He does not throw dice", which is commonly paraphrased as "God does not play dice with the universe." Supposedly, either Neils Bohr or Enrico Fermi remarked "Stop telling God what to do with his dice." - Source. And, Stephen Hawking remarked in a 1994 debate with Roger Penrose that "Consideration of black holes suggests, not only that God does play dice, but that he sometimes confuses us by throwing them where they can't be seen." Source.

Note: One shouldn't assume that the use of "God" by any of them means the notion of God commonly held by Christians today. But, their remarks do show that there has been much disagreement among eminent physicists regarding the role that chance plays in the universe.

If by chance most species of dinosaurs on earth had not been wiped out by a cataclysmic event, such as an asteroid strike on earth, 65 million years ago, the creatures posing the question "Do you really think that our existence is owed just to chance" might look something like one of the creatures depicted here.

We may simply be like that puddle mentioned by Douglas Adams.

>This is rather as if you imagine a puddle waking up one morning and thinking, 'This is an interesting world I find myself in - an interesting hole I find myself in - fits me rather neatly, doesn't it? In fact it fits me staggeringly well, must have been made to have me in it!' This is such a powerful idea that as the sun rises in the sky and the air heats up and as, gradually, the puddle gets smaller and smaller, it's still frantically hanging on to the notion that everything's going to be alright, because this world was meant to have him in it, was built to have him in it; so the moment he disappears catches him rather by surprise. I think this may be something we need to be on the watch out for. We all know that at some point in the future the Universe will come to an end and at some other point, considerably in advance from that but still not immediately pressing, the sun will explode. We feel there's plenty of time to worry about that, but on the other hand that's a very dangerous thing to say.

Source: Is there an Artificial God?

As to why humans tend to find certain environmental features beautiful, well natural selection offers an explanation.

>One of the most important considerations in the survival of any organism is habitat selection. Until the development of cities 10,000 years ago, human life was mostly nomadic. Finding desirable conditions for survival, particularly with an eye towards potential food and predators, would have selectively affected the human response to landscape—the capacity of landscape types to evoke positive emotions, rejection, inquisitiveness, and a desire to explore, or a general sense of comfort. Responses to landscape types have been tested in an experiment in which standardized photographs of landscape types were shown to people of different ages and in different countries: deciduous forest, tropical forest, open savannah with trees, coniferous forest, and desert. Among adults, no category stood out as preferred (except that the desert landscape fell slightly below the preference rating of the others). However, when the experiment was applied to young children, it was found that they showed a marked preference for savannahs with trees-exactly the East African landscape where much early human evolution took place (Orians and Heerwagen 1992). Beyond a liking for savannahs, there is a general preference for landscapes with water; a variety of open and wooded space (indicating places to hide and places for game to hide); trees that fork near the ground (provide escape possibilities) with fruiting potential a metre or two from the ground; vistas that recede in the distance, including a path or river that bends out of view but invites exploration; the direct presence or implication of game animals; and variegated cloud patterns. The savannah environment is in fact a singularly food-rich environment (calculated in terms of kilograms of protein per square kilometre), and highly desirable for a hunter-gatherer way of life. Not surprisingly, these are the very elements we see repeated endlessly in both calendar art and in the design of public parks worldwide.

Source: Aesthetics and Evolutionary Psychology

Or see Survival of the Beautiful: Art, Science, and Evolution by David Rothenberg

No, you certainly don't seem arrogant to me. I wouldn't assume just because someone has a different opinion on such matters that means he or she is arrogant. Nor do I downvote people just because their views don't match my own as I noticed someone did to your comments.

One of the reasons I visit reddit is to expose myself to others' viewpoints so that I can, hopefully, learn from doing so.

The claim that "time is exactly like space" is not true. Time is treated as a dimension in Special Relativity (SR) and General Relativity (GR), but it is very different from the "usual" spatial dimensions. (It boils down to "distance" along the time direction being negative, but that statement doesn't really mean anything out of context.) The central idea of relativity is that while the entire four dimensional "thing" (spacetime) just is (is invariant), different observers will have different ideas about which way the time direction points; it turns out to be convenient for our description of nature to respect the natural "democratic" equivalence of all hypothetical observers.

I can point you to a couple of good resources:

This

is a very good, book about SR, and some "other stuff". It's pretty mathematical, and I wouldn't recommend it to someone who isn't totally comfortable with college level intro physics and calculus.

This

is the "standard" text for undergraduate SR; it's less demanding than the above, but uses mathematical language that won't translate immediately if you go on to study GR. (I have not read this myself.)

This is the book that I learned from; I thought it was pretty good.

This is Brian Greene's famous popularization of String Theory. It has chapters in the beginning on SR and Quantum Mechanics that I think are quite good.

This is Einstein's own popularization, only algebra required. All the examples that others use to explain SR pretty much come from here, and sometimes it's good to go right to the source.

This is a collection of the most important works leading up to and including relativity, from Galileo to Einstein, in case you'd like to take a look at the original paper (translated). The SR paper requires more of a conceptual physical background than a mathematical one; the same can't be said of the included GR paper.

I don't know what your background is--the first three options above are textbooks, and that's probably much more than you were hoping to get into. The last three are not; the book by Brian Greene and the collection (edited by Stephen Hawking) are interesting for other reasons besides relativity as well. For SR, though, another book by Greene might be a bit better: this.

>"Don't be so quick to put us (theists/spiritualists) all in the same boat. There may be many more like me than you realize. Unfortunately, the more close minded, irrational among us tend to be the more vocal."

Also, more numerous: http://www.gallup.com/poll/155003/hold-creationist-view-human-origins.aspx

>"Yes I realize that the latter hold place in certain historical religions, but I really don't care about them, as they don't have anything to do with my beliefs. I do get that you are making the point that my beliefs now, ultimately, are just as fictional as those beliefs then. But I would say that it is a false equivalency, a slippery slope, to compare them. Any belief must be tested and judged on its own merit."

It's not so much "Dead religions are untrue, so currently relevant religions are also untrue" as it is "If you exhaustively study other religions you will see pervasive shared themes and implied psychology that the "somewhat smart" mistake for proof that all religions are divinely inspired and that the slightly more clever realize is proof that they were all authored by human beings."

Part of judging a belief system, in particular a holy text on it's own merits is giving it a read-through without the a priori assumption that it's correct on some level. Look at it instead as an anthropologist and psychologist, it is very revealing.

>"In fact, I'm suggesting that contemplation of this other realm is purely optional, that you don't need it for fulfillment in this realm, and that any conclusions about this other realm should not fly in the face of what we know about this realm."

In an ideal world. But what you've said is another way of saying "Don't treat it as if it's true, and it won't create problems". Other sincere, devout religious people you try to convert to this approach will sense that about it right away, like a cow catching a whiff of the slaughterhouse it's being led into.

>"Who am I?"

A mostly hairless self aware primate, part of a thin film of primates currently coating the globe for however long the oil holds out.

>"Why am I aware of myself?"

You have a sufficiently complex brain.

>"Where does my experience as an individual come from?"

The fact that your brain is physically separated from others and does not exchange information with them except by speech and writing.

>"How did the universe begin?"

Spontaneous particle and antiparticle separation events in an endless sea of quantum potential. "Do not keep saying to yourself, if you can possibly avoid it, 'But how can it be like that?' because you will get 'down the drain', into a blind alley from which nobody has yet escaped. Nobody knows how it can be like that." -Richard Feynman

>"Why is there something instead of nothing?"

Nothingness is maximally ordered. Collapse into somethingness was guaranteed by entropy. As for why entropy still applied back then, see the Feynman quote above.

>"I don't think science can answer these questions."

It's actually explained most of that and is working hard on the rest. I recommend picking up a copy of http://www.amazon.com/The-Grand-Design-Stephen-Hawking/dp/055338466X

>" It only simply gets at the fact that belief in a spiritual....something....may well satisfy certain philosophical questions that science can not. "

But does it? Simply offering up a story is not the same as explaining something. An explanation which cannot be shown to be true is not an explanation, it is a story. If you need to know a big bang occurred I can show you pictures of the lingering background radiation from it. If you need to know that matter and antimatter can spring from nothingness (insofar as we can tell at the moment) I can show it to you in a particle accelerator or at the event horizon of black holes in the form of Hawking Radiation. There's such a wealth of provable explanations on offer from science that the idea that some people take a story and treat it like an explanation because it's religious in origin is profoundly frustrating.

>"But I don't think these questions will ever be answered in any quantifiable, measurable way."

Even if that were true, it doesn't make a story legitimately equivalent to an explanation. Treating the story as true just because we don't have an explanation yet ignores the other, more sensible option of simply saying "we don't have it all figured out yet, and may never". I'll admit, "We don't know" is not satisfying. But that doesn't justify replacing it with pretend-knowledge.

>"But for those who chose to contemplate them, they must be answered spiritually. At least for now."

If, indeed, what they are doing can truthfully be called 'answering'.

> But if any one of them created something that is detectable, then I would have to say that the evidence of the existence of that entity would be the very things that they created.

Assuming you could show that the thing could only have been created by this otherwise undetectable thing. In practise, that's hard to do.

If we're speaking about the universe, cosmologists don't include a god in their calculations - they don't need one. You might check out Krauss' book A Universe From Nothing or a talk he did that has a lot of the same topics. Be warned - the talk is at an atheist convention so there are some jabs at Christianity. Stephen Hawking has an episode in the 'Curiousity' tv series where he explores whether or not a god is needed for a universe to exist.

> Who's to say that it won't be possible to create a "god microscope" that allows people to see god, someday in the future, if god is in fact see-able?

Well, if someone builds such a device and it provides credible evidence for a god, then you will never hear a religious person say "you just have to have faith" ever again. Until then, let's be reasonable and stick with what we have evidence for. For the rest we can be intellectually honest and say "we don't know."

> Who determines the value of the reasons? (Whether they're "good" or "bad" reasons?)

If you want to get really technical, there's epistemology which is the study of knowledge - how we know things and so on.

Ask yourself this: are some ways of gathering knowledge better than others? For instance, suppose I want to know how tall a particular building is. I could use:

And so on. Now, clearly, some of these are going to give me more accurate results, while some are going to be way off. Some might be sufficient depending on my needs. So if I tell you that I know the height of the 5-story building down the street from me because I divined it during a drug-induced trance, you're going to doubt my accuracy. If I told you that I had a trained surveyor use his equipment, you're probably going to think the number I have is reasonably accurate. If I'm a scientist, I might even give you error bars which tells you about how certain I am of my measurement.

So, I think people, using knowledge and reason are sufficiently capable of judging whether the reason we know things is sufficient or not. This might sound like circular reasoning but consider that if we have good reason to think a particular design of plane will fly and later it does fly, we can validate our reasoning with empiricism.

> But what would the point of existence be if there isn't something we're here for?

Suppose God does exist. Where does he get his purpose from? Does he require a god of his own to give him a purpose?

This question assumes there is a purpose. Why does there have to be? Why can't each individual person decide for themselves what they want their life to be about? As Sagan said,

> The significance of our lives and our fragile planet is then determined only by our own wisdom and courage. We are the custodians of life's meaning. We long for a Parent to care for us, to forgive us our errors, to save us from our childish mistakes. But knowledge is preferable to ignorance. Better by far to embrace the hard truth than a reassuring fable. If we crave some cosmic purpose, then let us find ourselves a worthy goal.

> I would suggest that it's pretty subjective in terms of what's "convincing" and what's not.

There are plenty of things that exist for which we have non-subjective evidence. The evidence that supports the idea that the Earth revolves around the sun is pretty convincing. No educated, rational person does not tentatively accept this proposition given the overwhelming amount of evidence to support it.

If you think a god exists, I would ask: what do you consider to be the most credible reason to think a god exists? If there are people who have examined your reasoning and have rejected it, what is it that is preventing them from holding your view? Is it stubbornness or a lack of information or experience, or is it something wrong with the argument itself, and so on?

I'm no physicist. My degree is in computer science, but I'm in a somewhat similar boat. I read all these pop-science books that got me pumped (same ones you've read), so I decided to actually dive into the math.

​

Luckily I already had training in electromagnetics and calculus, differential equations, and linear algebra so I was not going in totally blind, though tbh i had forgotten most of it by the time I had this itch.

​

I've been at it for about a year now and I'm still nowhere close to where I want to be, but I'll share the books I've read and recommend them:

​

I'm available if you want to PM me directly. I love talking to others about this stuff.

There's also the cyclic model; there's also a Wikipedia article on the cyclic model. That model seems to mesh better with Hinduism.

>If you are a Hindu philosopher, none of the above should surprise you. Hindu philosophy has always accepted the notion of an alternately expanding and contracting universe. In his book Cosmos, Carl Sagan pointed out how, in Hindu cosmology, the universe undergoes an infinite number of deaths and rebirths, and its timescales are in the same ballpark as those of modern cosmology. Here is a quote from Cosmos:

>

>"There is the deep and appealing notion that the universe is but a dream of the god who, after a hundred Brahma years, dissolves himself into a dreamless sleep. The universe dissolves with him - until, after another Brahma century, he stirs, recomposes himself and begins again to dream the cosmic dream.

>

>Meanwhile, elsewhere, there are an infinite number of universes, each with its own god dreaming the cosmic dream. These great ideas are tempered by another, perhaps greater. It is said that men may not be the dreams of gods, but rather that the gods are the dreams of men."

Reference: The Conscious Universe: Brahma's Dream

Or for the Big Bang model, one might address the question as Steven Hawking has in his book The Grand Design.

>He adds: "Because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing.

>

>"Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing, why the universe exists, why we exist.

>

>"It is not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touch paper and set the universe going."

Reference: Stephen Hawking: God did not create Universe

In any case, one can ask "where did God" come from as well. One can say "God has always existed", but one can say the universe always existed or there were other universes before this one, etc., also. Our limited intellects and knowledge of the universe may keep humans from truly knowing the answer indefinitely.

I. Sure, some forms of theism are coherent (Christianity is not one of those forms, for what it's worth; the Problem of Natural Evil and Euthyphro's Dilemma being a couple of big problems), but not all coherent ideas are true representations of the world; any introductory course in logic will demonstrate that.

II. The cosmological argument is a deductive argument. Deductive arguments are only as strong as their premises. The premises of the cosmological argument are not known to be true. Therefore, the cosmological argument should not be considered true. If you think you know a specific formulation of the cosmological argument that has true premises, please present it. I'm fully confident I can explain how we know such premises are not true.

III. There is no doubt that the teleological argument has strong persuasive force, but that's a very different thing than "being real evidence" or "something that should have strong persuasive force." I explain apparent cosmological fine-tuning as an entirely anthropic effect: if the constants were different, we wouldn't be here to observe them, therefore we observe them as they are.

IV. This statement is just false on its face. Lawrence Krauss has a whole book about the potential ex nihilo mechanisms (plural!) for the creation of the universe that are entirely consistent with the known laws of physics. (Note that the idea of God is not consistent with the known laws of physics, since he, by definition, supersedes them.)

V. This is just a worse version of argument III. Naturalistic evolution has far, far more explanatory power than theism. To name my favorite examples: the human blind spot is inexplicable from the standpoint of top-down design, but it makes perfect sense in the context of evolution; likewise, the path of the mammalian nerves for the tongue traveling below the heart makes no sense from the standpoint of top-down design, but it makes perfect sense in the context of evolution. Evolution routinely makes predictions that are tested to be true, whether it means predicting where fossils with specific characteristics will be found or how fruit fly mating behavior changes after populations have been separated and exposed to different environments for 30+ generations. It's worth emphasizing that it is totally normal to look at the complexity of the world and assume that it must have a designer...but it's also totally normal to think that electrons aren't waves. Intuition isn't a reliable way to discern truth. We must not be seduced by comfortable patterns of thought. We must think more carefully. When we think more carefully, it turns out that evolution is true and evolution requires no god.

VI. There are two points here: 1) the universe follows rules, and 2) humans can understand those rules. Point (1) is easily answered with the anthropic argument: rules are required for complex organization, humans are an example of complex organization, therefore humans can only exist in a physical reality that is governed by rules. Point (2) might not even be true. Wigner's argument is fun and interesting, but it's actually wrong! Mathematics are not able to describe the fundamental behavior of the physical world. As far as we know, Quantum Field Theory is the best possible representation of the fundamental physical world, and it is known to be an approximation, because, mathematically, it leads to an infinite regress. For a more concrete example, there is no analytic solution for the orbital path of the earth around the sun! (This is because it is subject to the gravitational attraction of more than one other object; its solution is calculated numerically, i.e. by sophisticated guess-and-check.)

VII. This is just baldly false. I recommend Dan Dennett's "Consciousness Explained" and Stanislas Dehaene's "Consciousness and the Brain" for a coherent model of a materialist mind and a wealth of evidence in support of the materialist mind.

VIII. First of all, the idea that morality comes from god runs into the Problem of Natural Evil and Euthyphro's Dilemma pretty hard. And the convergence of all cultures to universal ideas of right and wrong (murder is bad, stealing is bad, etc.) are rather easily explained by anthropology and evolutionary psychology. Anthropology and evolutionary psychology also predict that there would be cultural divergence on more subtle moral questions (like the Trolley Problem, for example)...and there is! I think that makes those theories better explanations for moral sentiments than theism.

IX. I'm a secular Buddhist. Through meditation, I transcend the mundane even though I deny the existence of any deity. Also, given the diversity of religious experience, it's insane to suggest that religious experience argues for the existence of the God of Catholicism.

X. Oh, boy. I'm trying to think of the best way to persuade you of all the problems with your argument, here. So, here's an exercise for you: take the argument you have written in the linked posts and reformat them into a sequence of syllogisms. Having done that, highlight each premise that is not a conclusion of a previous syllogism. Notice the large number of highlighted premises and ask yourself for each, "What is the proof for this premise?" I am confident that you will find the answer is almost always, "There is no proof for this premise."

XI. "...three days after his death, and against every predisposition to the contrary, individuals and groups had experiences that completely convinced them that they had met a physically resurrected Jesus." There is literally no evidence for this at all (keeping in mind that Christian sacred texts are not evidence for the same reason that Hindu sacred texts are not evidence). Hell, Richard Carrier's "On the Historicity of Christ" even has a strong argument that Jesus didn't exist! (I don't agree with the conclusion of the argument, though I found his methods and the evidence he gathered along the way to be worthy of consideration.)

-----

I don't think that I can dissuade you of your belief. But, I do hope to explain to you why, even if you find your arguments intuitively appealing, they do not conclusively demonstrate that your belief is true.

How the universe was made?

I think the real crux of the question you're asking is how can something come from nothing? (feel free to correct me if I'm wrong; I don't want to speak for you) Let me just start off by saying there is no definitive scientific answer to this question... yet. However, there are very prominent research scientists who have tackled the question and come up with very cogent theories (backed up by current mathematical models).

I won't pretend to understand most of these theories as I'm a biologist, not a physicist. There is one recent book written on the very topic called A Universe from Nothing by Lawrence Krauss (he is a published theoretical physicist and cosmologist). He posits that particles do in fact spontaneously come into existence and there is scientific proof and reasoning for how and why. I haven't gotten around to reading it myself (it was just published this year), but I've been told it's good for the layman on the topic.

Now let me move on to some of the problems with this question. Perhaps you yourself don't have this supposition, but the supposition many theists make with the question (where did the universe come from?), is that if it can't be answered than God must have done it. This is a logical leap that defies rational reasoning, and is a leap theists have been making for millenia. What makes the tides go in and out? We don't know; must be God. What causes disease? We don't know; must be God. Where did the universe come from? We don't know; must be God?

It's what's known as a God of the gaps; wherein anything that can't be explained is conveniently claimed to have a divine explanation. Until a rational scientific answer comes along and religion takes a step back. There will likely always be gaps in our knowledge base (most definitely in our liftetimes). That doesn't mean we should make the same mistake as our ancestors and attribute these gaps to God. It's okay to simply not know and strive to understand.

Another huge problem with your question is that the theist answer only serves to further complicate the original question.

Theists tend to skip that third step, or explain it away as God just always existing. Yet the universe always existing is something that is logically unacceptable to them. If anything, throwing God into the equation only makes it more complicated. A sentient being capable of creating the initial state of the universe would be more complex than what it is creating (meaning God is more complex than the universe). Trying to explain than how God came into being is more complicated than the original question, so nothing has really been answered or solved.

If you're really trying to stump atheists, the best common theist argument I've seen is the cosmological constants one (how are they so fine tuned?). No doubt there are answers, but that's one of the better arguments out there. I won't go into it here, just search for it.

It can be explained, though not simply, nor accessibly. Luckily, I'm not just an atheist, I'm also a theoretical physics student. Keep in mind that this of course can not be demonstrated empirically (science is the study of our Universe, so we obviously can't study things outside it in time or space).

Lets go back to before the Universe exists. Let's call this state the Void. It's important to note that no true void exists in our Universe, even the stuff that looks empty is full of vacuum fluctuations and all kinds of other things that aren't relevant, but you can investigate in your own time if you want. In this state, the Void has zero energy, pretty much by definition. Now, the idea that a Void could be transforms into a Universe is not really controversial; stuff transforms by itself all the time. The "problem" with a Universe arising from a Void is that the Universe has more energy than the Void, and it there's not explanation for where all this energy came from. Upon further investigation, we'll actually see that the Universe has zero net energy, and this isn't actually a problem.

Now, let's think about a vase sitting on a table. One knock and it shatters, hardly any effort required. But it would take a significant amount of effort to put that vase back together. This is critically important. Stuff has a natural tendency to be spread out all over the place. You need to contribute energy to it in order to bring it together. We're going to call this positive energy.

Gravity is something different though. Gravity pulls everything together. Unlike the vase, you'd need to expend energy in order to overcome the natural tendency of gravity. Because it's the opposite, we're going to call gravity negative energy. In day to day life, the tendency of stuff to spread out overwhelms the tendency of gravity to clump together, simply because gravity is comparatively very weak. There's quite a few more factors at play here, but stuff and gravity are the important ones.

Amazingly, it turns out that it's possible for the Universe to have exactly as much negative energy as it does positive energy, which means that it would have zero total energy, meaning that it's perfectly possible for it to pop out of nowhere, by dumb luck, because no energy input is required. Furthermore, we know how to check if our Universe has this exact energy composition. And back in 1989, that's exactly what cosmologists did. And it turns out it does. We can empirically show, to an excellent margin of error, that our Universe has zero net energy. Think about that for a second. Lawrence Krauss has a great youtube video explaining the evidence for this pretty incredible claim.

The really incredible thing is, given that our Universe has zero net energy, it's not only possible that it could just pop into existence on day, it's inevitable. It's exactly what we'd expect. Hell, I'd be out looking for God's fingerprints if there wasn't a Universe, not the opposite.

If you want to read more about it, by people who've spent far more time investigating this than I have, I suggest The Fabric of the Cosmos by Brian Greene, and A Universe From Nothing: Why There Is Something Rather Than Nothing by Lawrence Krauss. Both go into detail about the subject, and don't require any prior physics knowledge.

tl;dr The Universe didn't need a "first cause". PHYSICS!

A little more than ELI5 but worth the effort, Kip Thorne, the physicist who consulted on the film, wrote a fantastic book that covers this question in depth.

You can read it here.

I recommend reading the entire Prologue since it's relatively short and pretty fascinating, and will give you the background to why it must be a very large black hole, but the part directly relevant to your question is the section entitled Gargantua on page 41. (Also relevant is the establishing of the problem on pp. 34-35)

If you like his writing, buy his book Black Holes and Time Warps. The link above is just some random PDF I found on a search.

To sum him up though, a super-massive black hole will have negligible tidal forces at its "surface" (event horizon). You therefore could hover just above it and not be spaghettified. Once you cross the horizon, you'd still be okay for a while, but now no amount of force could keep you from falling ever closer to the center. As you approached the center, tidal forces would increase exponentially until eventually you would be pulled apart. So yes, it would be gentle. At first. But once you go inside, spaghettification is inevitable, though not necessarily immediate.

TL:DR A big size to make it more gentle? Yes. Possible to enter without spaghettification? Temporarily yes, ultimately no.

Submission Statement: On November 2016, David Deutsch and Sam Harris did a podcast together. The purpose of that podcast was for David Deutsch to attempt to explain where Sam Harris went wrong or could improve upon his The Moral Landscape idea.

David is a Popperian and has built upon Popper’s work in his two books The Fabric of Reality and The Beginning of Infinity. This podcast sparked my interest in Popper and at the time I did not understand the disagreement between David and Sam. I asked the question and Brett Hall who is an expert (doubt he’d enjoy that label) on Popper and Deutsche was kind enough to make a video explaining their differences.

The reason I decided to transcribe this video is that I have found that comparing and contrasting Sam’s epistemology to that of Popper’s has been super helpful in better understanding Critical Rationalism, which is what Popper called his Philosophy. I have read Popper and Deutsch for a year since and have barely scratched the surface.

You do not necessarily need to listen to the Podcast to get the meat of this content, Brett does a great job presenting both their ideas clearly and their differences as well.

Anyway, here are some interesting bits from the video.

>The majority of people who have an alternative epistemology, something other than what Karl Popper views knowledge as for example, they think that knowledge is about justified true belief. They think that you need to begin with the foundation and on that foundation then you accumulate knowledge, you build it up. And this is an anti critical vision about how knowledge is created. In the Popperian view, you simply have problems, you can start anywhere at all and you attempt to solve those problems when you have them. When you have ideas that are in conflict with one another by using a critical method, it's a completely different vision.

On What Morality is,

>So instead, just to preface, what morality really consists of, it's about solving moral problems. And in order to solve moral problems, we have to conjecture explanations about what might improve things. And they can always be false. We can always criticize them.

There is no need for bedrock,

>Okay. So again, David says that moral theory should be approached like scientific theories. They don't need foundations. They don't need foundations. There are a lot of theories out there, a lot of moral theories like, Kant's categorical imperative, or Rawl's fairness or stuff that comes out of the Bible the golden rule et cetera, et cetera. Whatever your moral theory happens to be or indeed Sam's wellbeing of conscious creatures. All of these, these principles, these ideas, these theories should be seen as critiques, as critiques of each other or as critiques of any other theory that someone proposes or as a critique of a solution that someone proposes.

>

>They shouldn't be seen as foundations from which you begin to build up everything else.

There is a lot of great information in here not just about morality, there’s a bit about politics, creativity, and perhaps most groundbreaking in my estimation, David’s explanation of what a person is.

I hope this is helpful!

Other Links:

> I mean from what I know scientifically is the big bang theory and that in itself is pretty questionable.

That couldn't be further from the truth. The Big Bang Theory is one of the most widely accepted theories in science because the evidence to back it up is too strong. Did you know that the theory made very specific predictions about what we would find if we looked for very specific data, and then we looked for it and turns out we would out exactly what the Big Bang Theory predicted we would? That's why scientists accept it as better than other theories. Because it makes good testable predictions, we have tested this predictions, and they every time, they confirm the Big Bang. In fact, the Big Bang Theory used to be widely discredited by scientists for many decades in favor of other theories, until we finally found actual evidence to support it. Then everyone changed sides. So it's not like scientists just believe on the Big Bang out of thin air. They accept it because it's by far the best theory we have today with the most evidence behind it.

You're making the classic mistake of confusing a "theory" with a "hypothesis". In science the word "theory" is not arbitrary, you can't call whatever arbitrary idea in your head a "theory". It has to go through meticulously high standards to be able to even be considered a theory. One example, is that it needs to make new observable predictions, or else, it's just a hypothesis, not a theory. "A wizard did it" is a hypothesis, Big Bang is a theory. A theory is necessarily always better than a hypothesis. And one theory can be better than others, one might have more stronger evidence to back it up. In the case of the Big Bang, it has a lot of very strong evidence.

> theres no scientific explanation for an actual starting point where nothing existedm just vaccuum.

Actually there is. That's part of the Big Bang Theory. It's not a simple explanation as it requires advanced modern scientific understanding. Basically "time" is not an infinite constant as we used to think centuries ago. Time is variable depending on speed and it has an actual starting point where there's nothing before that. That starting point is the Big Bang. The Big Bang is the beginning of time itself. So it doesn't make sense to ask what was "before" it, because there was no time for anything to be before about.

"Asking what was there before the Big Bang is like asking what is north of the north pole." -- Stephen Hawking

It's also not "nothing existing just vacuum", it's the exact opposite of that. It was everything, not nothing. Literally the whole universe was in just this one spot called the singularity. That's far from "nothing".

You might be thinking "that sounds crazy, do we have any evidence of that?". Yes we do, a lot of it actually. For one example, the GPS in your phone would not be working if this theory wasn't true. Because the calculations to determine the position of satellites were predicted by the same theory, turns out they work. If you want to, you can read about it directly from the person who came up with the explanation and its predictions in the first place. Stephen Hawking explains the beginning of the universe on his book Grand Design:

http://www.amazon.com/The-Grand-Design-Stephen-Hawking/dp/055338466X

Check out the Foundational Falsehoods of Creationism.

Check out a copy of the books The Greatest Show on Earth or Why Evolution is True from a library. You can also get one of them for free on Audible, but you will miss out on the citations and diagrams.

See if you can watch or read The Grand Design by Stephen Hawking. I watched the miniseries, it's pretty good. It used to be on Netflix but no longer is.

Cosmos is great, and is on Netflix. If you want to watch videos about Cosmology just type in one of the popular physicist's names, Brian Greene, Neil deGrasse Tyson, Lawrence Krauss (his Universe from Nothing book is really great, so are his lectures about it), Sean Carroll etc.

Let me know if you want to talk, I'm always up for it.

> If there isnt a creator then how did all this life get here?

Abiogenesis is our best working guess for now, but there's a lot of work left to be done. The key thing here though is to be honest and admit that we don't have all the answers rather than wave our hands and say that it was a magical sky faerie.

> I under stand the big bang, at one point all the matter in Universe was compact then it all expanded outwards, well from school I learned that matter cannot be created nor destroyed. How did all that compact matter get there in the first place? I dont know.

It's ok to not know - that's honesty. This excellent book by Lawrence Krauss is fascinating. If you don't have access to it, there's also a talk he gave a few years back.

> I guess I'm getting old enough where my own opinions are forming I'm just trying to decide what I want those opinions to be.

Remember that ultimately our opinions are just that - opinions. The universe is as it is regardless of what we may wish to be true and what we may believe.

I agree. :-) I figured I'd pick a fairly strong example of easily shot down attributes. (On the other hand, the fact that at least 1/3 of the voters in my country agree with the easily shot down version is quite scary, but that's a rant for another day ;-)

The reasons I reject Christianity as a whole are much larger, and not really applicable here, but since you brought it up:

I was born and raised an evangelical Christian, and remained so for ~25 years after my decision at 7 to accept Jesus's death as atonement for my sins and follow him with my whole life.

I am no longer for many reasons, starting with accepting evolution and the lack of an historical Adam, moving into biblical criticism and archeological study, studying other world religions and cultures and their similar claims to Christianity, studying cosmology, psychology, sociology, and cognitive science of religion, and ending at philosophy and specifically epistemology. I tried really hard to maintain my faith, but there is no grounding for it that I can find, and I gave it up with much grief.

Christianity is in no way exceptional to all the other religions. In that way I agree with Spong's 12 points of reform. If you don't know why Spong talks like that, his book Why Christianity Must Change or Die speaks at least as strongly as the atheist polemics. In addition, as I understand the reasons for apparent teleology and cognitive basis for religion which arose by co-opting the social mechanisms of our brain given by natural selection, and think there is a rising case for the universe spontaneously springing out of a quantum foam which is a much less problematic thing to pre-exist than a conscious, changeless entity of incredible knowledge, power, and perfection. Not to mention the issues of causality and intentionality existing in such a creature outside space-time and the entropic arrow of time, without which causality is incoherent. It is for this reason that much of the most interesting theology in the journals these days is on time issues.

Because of all these things we now have much simpler answers for than a supreme being, I see absolutely no reason to posit even a panenthesitic, pantheistic, or deistic god. The later two, even if existant, would by definition have absolutely no impact on my life, and the first no measurable impact.

In the end, if all religion can possibly discover is that we should to be nice to each other and feel awe of the universe and love, I'll take other moral theories that give me the same and yet come from grounding in the observable universe, thanks. Desire utilitarian theory is one of the more interesting ones.

I think the Atheist's Guide to Reality linked above is perhaps the most important book I've ever read which argues strongly goes against the typical arguments of the apologists, and I'm anxious to see more people critique it. Krauss's book linked above is one of very few I've ever pre-ordered, as his video with the same title was quite interesting. If he has a good basis for his claims, it might be the most important scientific theory since Darwin in relation to understanding ourselves.

Nothing about your claims of "self-evidence" is true in my case.

> These beliefs are ones you cannot help but believe; for example, the belief that you exist.

Descartes? "I think, therefore I am?" That's evidence, not self-evidence (though it is evidence for self.) I find it convincing; but then I have a strong bias. This isn't about sufficiency of evidence though; it's about evidence vs. self-evidence.

But how do you take it beyond that? How do you extend it to observations, to the universe, to reality? There are two choices there:

> Most of us also posses pragmatism as a self-evident belief.

"Most" people don't think about it at all. "Most" people are content to think their smartphones are magic. Scientists aren't most people. I'm no most people. And if you're thinking about this topic enough to have this conversation, you're not most people in this respect either. So let's look beyond the pragmatism of "not thinking about epistemology and empiricism won't get me eaten by a tiger, so why bother" and get on with the conversation.

I do consider the possibility the universe is a simulation, or that I'm a brain in a jar being fed stimulus (Actually it's hard to distinguish that testably from surfing reddit, but I digress.) Why not? But those avenues of thought don't lead very far; I feel I've considered them sufficiently. They haven't lead to useful insights yet (saving perhaps the holographic principle), but I remain open to the possibility. Pragmatism has it's place; you can't philosophies if you don't pay attention to things like not dying, but that's evidence for its necessity, not its sufficiency. Think further.

> Why is the sky blue? Because you see it as blue. How do you know that it actually is blue? You don't, but you [presumably] find it self-evidently more rational to assume that what you see is representative of reality, via pragmatism, or a similar philosophy.

And this is where I differ vastly from your preconceived notions of me. I believe the sky is blue because, when I was nine, I built a crude spectroscope and measured it (It's actually mostly white, by the way, with a small but significant increase in the intensity of blue light over what is expected of black-body radiation. Not counting sunset of course. And neglecting absorption lines - I was in third grade, the thing wasn't precise enough for that!)

So that's evidence the sky is blue (and that I was an unusual kid), not "self-evidence." Although in this case, actually observing the sky with your eyes is still evidence; our eyes may be flawed in many ways, but they are sufficient for distinguishing between at least a few million gradations between 390-700 nm wavelengths. That's quite sufficient for narrowing it down to "blue."

That's exactly what I mean about what people consider "self-evidence" actually being evidence they've seen so often they've forgotten it's evidence. You note the approximate visible wavelength of the sky many times a day; it's actually quite well established by repeated observation that (barring systematic errors in our visual processes) it's blue.

> But, if someone did not share this self-evident belief, they would find it quite irrational to assume that the sky is indeed blue in reality, as opposed to merely in your perception of it.

So let's say this happened - let's say someone said the sky was green. Well, there are two possibilities, and we can distinguish between them by showing them other objects with similar emission or reflection spectra. One is that they see these other purportedly blue objects as green. No problem! They simply use "green" to mean "blue." Half a billion people use azul instead, so this is no big deal.

The other possibility is that every other blue thing we can test looks blue to this person, but they still insist the sky is green. This again leads to two possibilities. One is that the sky really is green just for this individual and most of what we have determined about reality is false. The other is that this person has a psychological condition that makes him believe the sky is green. Do we have to accept that the sky is simply self-evidently green to him? Nope! Science!

Put him in a room, and through one slit allow in natural sunlight, and through another match the spectrum of solar light with artificial light as closely as possible. Vary which slit is which. Can this person regularly identify the "green" sky? (specifically compared to control groups?) If not, we can conclude he sees the sky as green due to a psychological condition, not something indicative of reality. This is surprisingly common - just read up on dowsing for instance. There are people convinced they can detect water with sticks, but every one of them fail in tests to do so at rates above random chance. (Dowsers got away with this in old days because when you dug a well, you'd only have to hit a state-sized aquifer.)

The alternative, if he can regularly identify the sky slit as green, and assuming that other possibilities have been excluded, is that reality really doesn't work the way we think it does. Maybe he's a separate brain in a separate jar. Maybe light waves like certain people better. Maybe what we thought were photons were just faeries and they're screwing with us for fun. Whatever the case, though, we'd now have evidence for it. Not "self-evidence" but actual evidence.

Now, you can argue that maybe reality doesn't matter - maybe that person's psychological condition that makes him see a green sky is just as important as the blue sky. Maybe it makes him happier or donate to charity more or whatever, so we should leave him alone. All fine arguments, but they would be separate discussions.

From your other link:

> I also concluded that by logic, existence itself is uncaused.

That remains to be seen. Well-tested theories still leave open other possibilities; though obviously we haven't yet tested these possibilities. But since your basis for belief, according to the other thread, was on the necessity of an uncaused creation in violation of natural laws, I thought you might be interested to know that there are some hypothesis regarding said creation that fit within those laws.

> I know counter points to the popular atheist verses

Umm, are you talking about the bible? Those are biblical verses, not atheist verses, unless you're saying god inspired atheist verses!

Anyway, that sounds like a challenge: